By Robert Draper – this story appears in the February 2018 issue of National Geographic magazine.

Technology and our increasing demand for security have put us all under surveillance. Is privacy becoming just a memory?

A high-definition camera tracks a hired subject along a street in Islington, a borough in Greater London.

Two closed-circuit television system operators monitor Islington’s control room, where they can watch images from the borough’s extensive camera network. London’s video surveillance helped solve the deadly 2005 terrorist bombings, which killed 52 people.

PHOTOGRAPH BY TOBY SMITH

….

In 1949, amid the specter of European authoritarianism, the British novelist George Orwell published his dystopian masterpiece 1984, with its grim admonition: “Big Brother is watching you.” As unsettling as this notion may have been, “watching” was a quaintly circumscribed undertaking back then. That very year, 1949, an American company released the first commercially available CCTV system. Two years later, in 1951, Kodak introduced its Brownie portable movie camera to an awestruck public.

Today more than 2.5 trillion images are shared or stored on the Internet annually—to say nothing of the billions more photographs and videos people keep to themselves. By 2020, one telecommunications company estimates, 6.1 billion people will have phones with picture-taking capabilities. Meanwhile, in a single year an estimated 106 million new surveillance cameras are sold. More than three million ATMs around the planet stare back at their customers. Tens of thousands of cameras known as automatic number plate recognition devices, or ANPRs, hover over roadways—to catch speeding motorists or parking violators but also, in the case of the United Kingdom, to track the comings and goings of suspected criminals. The untallied but growing number of people wearing body cameras now includes not just police but also hospital workers and others who aren’t law enforcement officers. Proliferating as well are personal monitoring devices—dash cams, cyclist helmet cameras to record collisions, doorbells equipped with lenses to catch package thieves—that are fast becoming a part of many a city dweller’s everyday arsenal. Even less quantifiable, but far more vexing, are the billions of images of unsuspecting citizens captured by facial-recognition technology and stored in law enforcement and private-sector databases over which our control is practically nonexistent.

Those are merely the “watching” devices that we’re capable of seeing. Presently the skies are cluttered with drones—2.5 million of which were purchased in 2016 by American hobbyists and businesses. That figure doesn’t include the fleet of unmanned aerial vehicles used by the U.S. government not only to bomb terrorists in Yemen but also to help stop illegal immigrants entering from Mexico, monitor hurricane flooding in Texas, and catch cattle thieves in North Dakota. Nor does it include the many thousands of airborne spying devices employed by other countries—among them Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea.

We’re being watched from the heavens as well. More than 1,700 satellites monitor our planet. From a distance of about 300 miles, some of them can discern a herd of buffalo or the stages of a forest fire. From outer space, a camera clicks and a detailed image of the block where we work can be acquired by a total stranger.

Simultaneously, on that very same block, we may well be photographed at unsettlingly close range perhaps dozens of times daily, from lenses we may never see, our image stored in databases for purposes we may never learn. Our smartphones, our Internet searches, and our social media accounts are giving away our secrets. Gus Hosein, the executive director of Privacy International, notes that “if the police wanted to know what was in your head in the 1800s, they would have to torture you. Now they can just find it out from your devices.”

….

“If you want a picture of the future,” Orwell darkly warned in his classic, “imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.” This authoritarian vision discounts the possibility that governments might use such tools to make the streets safer. Recall, for example, the footage from security cameras that cracked the cases of the 2005 London subway and 2013 Boston Marathon bombings. Multitudes of more obscure episodes exist, such as that of Euric Cain, caught unambiguously on camera shooting a Tulane University medical student named Peter Gold in 2015 after Gold prevented him from abducting a woman on the streets of New Orleans. (Gold survived; Cain received a 54-year prison sentence for a crime rampage that included rapes, armed robbery, and attempted murder.)

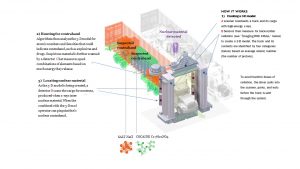

At the Port of Boston, the Department of Homeland Security has tested a cargo-visualizing method invented by two MIT physicists, Robert Ledoux and William Bertozzi. Using a technique known as nuclear resonance fluorescence—in which elements become identifiable by exciting their nuclei—the screening device can, without opening a freight container, discern the elemental fingerprint of its contents. Unlike a typical x-ray scan, which shows only shape and density, it can tell the difference between soda and diet soda, natural and manufactured diamonds, plastics and high-energy explosives, and nonnuclear and nuclear material.

At the Port of Boston, the Department of Homeland Security has tested a cargo-visualizing method invented by two MIT physicists, Robert Ledoux and William Bertozzi. Using a technique known as nuclear resonance fluorescence—in which elements become identifiable by exciting their nuclei—the screening device can, without opening a freight container, discern the elemental fingerprint of its contents. Unlike a typical x-ray scan, which shows only shape and density, it can tell the difference between soda and diet soda, natural and manufactured diamonds, plastics and high-energy explosives, and nonnuclear and nuclear material.

Does anyone doubt that a more closely inspected world over the past 150 years would have been a safer one? We might know the identity of Jack the Ripper, whether Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone, and if O. J. Simpson acted at all. Of course, public safety has been the pretext for surveillance before and since Orwell’s time. But today such technology can be seen as a lifesaver in more encompassing ways. Thanks to imagery provided by satellite cameras, relief organizations have located refugees near Mosul, encamped in the deserts of northern Iraq. And thanks to numerous space probes, scientists have proof that the world’s climate is dramatically changing.

….

‘There is an appetite in the U.K. for surveillance that I haven’t seen anywhere else in the world,” said Tony Porter, the world’s only known surveillance camera commissioner, as we sat in the cafeteria of a London government office with CCTV cameras peering at us from the corners. A former police officer and counterterrorism specialist, Porter was recruited four years ago by Her Majesty’s Home Office, responsible for the security of the realm, to lend a semblance of oversight to the country’s ever growing surveillance state. With a paltry annual budget of $320,000, Porter and three staffers spend their workdays persistently urging, with some success, government and commercial users of surveillance cameras to comply with the relevant codes and guidelines. But beyond mentioning the names of the noncompliant in a report to Parliament, Porter’s office has no powers of enforcement.

Nonetheless, his appraisal of the U.K. as the most receptive country in the world to surveillance technology is widely shared. London’s network of surveillance cameras was first conceived in the early nineties, in the wake of two bombings by the Irish Republican Army in the city’s financial district. What followed was a fevered spread of monitoring technology. As William Webster, a professor of public policy at the University of Stirling in Scotland and an expert on surveillance, recalls, “The rhetoric about public safety at the time was, ‘If you’ve got nothing to hide, you’ve got nothing to fear.’ In hindsight, you can trace that slogan back to Nazi Germany. But the phrase was commonly used, and it crushed any sentiment against CCTVs.”

….

Elements of fear and romance help explain the profusion of surveillance in the U.K. This, after all, is a country saved by espionage: The museum commemorating the legendary World War II code breakers at Bletchley Park, 40 miles northwest of London, is today a much visited site. So, for that matter, is the London Film Museum’s permanent exhibit on the dashing spy James Bond, a creation of the writer and former British naval intelligence officer Ian Fleming. Agent 007 is bound up in the nation’s postwar self-appraisal, but so is the jolting reality that the U.K. was one of the first countries to face the constant fear of terrorist attacks. When it comes to protecting its people, the British government is viewed in a more appreciative light than perhaps those of other free societies. Even after the revelations by former U.S. National Security Agency contract employee Edward Snowden that American and British intelligence agencies had been collecting bulk data from their own citizens—a disclosure that triggered calls for reform by both political parties in the U.S.—Parliament essentially enshrined those powers in late 2016 by passing the Investigatory Powers Act with scant public outcry.

…..

That’s not by any means to say that a country like the United States, with its more skeptical view of big government, is wholly immune to surveillance creep. Most of its police departments are now using or considering using body cameras—a development that, thus far at least, has been cheered by civil liberties groups as a means of curbing law enforcement abuses. ANPR cameras are in many major American cities as traffic and parking enforcement tools. In the wake of the September 11 attacks, New York City ramped up its CCTV network and today has roughly 20,000 officially run cameras in Manhattan alone. Meanwhile, Chicago has invested heavily in its network of 32,000 CCTV devices to help combat the murder epidemic in its inner city.

But other U.S. cities with no history of terrorist attacks and relatively low violent crime rates also have embraced surveillance technology. I checked out the CCTV network that has quietly spread throughout downtown Houston, Texas. As recently as 2005, the city didn’t have a single such camera. But then Dennis Storemski, the director of the Mayor’s Office of Public Safety and Homeland Security, began touring other cities. “Basically, it was what I saw in London that got me interested in the technology,” he recalls. Today, thanks to federal grants, Houston has 900 CCTV cameras, with access to an additional 400. As in London, officials don’t monitor every camera every minute—and as such, Storemski says, “it’s not surveillance per se. We’ve wanted to take away the expectation that people are watching.” Perhaps for that reason, Houston’s CCTV reach will soon expand well beyond downtown, but—in a state hardly known as trusting of government—without the slightest drama.

….

Outside of the city in the county of South Yorkshire, I visited Barnsley Hospital, where some security personnel are equipped with body cameras to discourage unruly behavior by patients or visitors. Similar cameras, it was reported during my stay, were being tested for use by schoolteachers. Given that an estimated 150,000 British police officers are already equipped with such devices, perhaps it’s an effortless next step to contemplate them on other authority figures, such as educators and nurses. From there, however, who’s next? Flight attendants? Postal workers? Psychologists? Human resource directors?

“Some local authorities are seeking to compel taxi drivers to use surveillance,” Porter, the surveillance camera commissioner, told me. “Considering that, and the use of body cameras in hospitals and schools, the question I’d put forward is: What kind of society do we want to live in? Is it acceptable for all of us to go around legitimately filming each other, just in case somebody commits a wrong against us?”

….

The seemingly minute-by-minute advancements in surveillance technology can, to some civil libertarians, take on the appearance of a runaway bullet train. As Ross Anderson, professor of security engineering at the University of Cambridge, warns, “We need to be thinking ahead to the next 20 years. Because that’s when you’ll have augmented reality, an Oculus Rift 2.0, with at least 8,000 pixels per inch. So, sitting in the back of a lecture hall, you can read the text on a lecturer’s phone. At the same time, the one hundred CCTVs in that lecture hall will be able to see the password you’re punching into your phone.”

Even Huxley, whose masterwork presents a forbidding view of a hyper-industrialized London in the year 2540, didn’t conceive of a world so acutely visualized that our most intimate secrets can’t always be concealed. Where would that leave us? On the one hand, it stretches credulity to imagine the willful suppression of such tools. Says David Anderson, a London barrister who spent six years as the government’s independent reviewer of counterterrorism legislation, “Either you think technology has presented us with strong powers that the government should use with equally strong safeguards, or you believe this technology is so scary we should pretend it’s not there. And I’m firmly in the first category—not because I say government is to be trusted, but instead because in a mature democracy such as this one, we’re capable of constructing safeguards that are good enough for the benefits to outweigh the disadvantages.”

On the other hand, allowing such technological progress to find its way into a largely unregulated marketplace seems equally imprudent. Jameel Jaffer, the founding director of Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Institute, says, “I do think that we live increasingly recorded and tracked lives. And I also think we’re only starting to grapple with the implications of that, so before we adopt new technologies or before we permit new surveillance forms to entrench themselves in our societies, we should think about what the long-term implications of those surveillance technologies will be.”

How to craft such judgments? Endeavoring to do so is particularly nettlesome when a breakthrough occurs that explodes our notion of how we can view the world. In fact, a game changer of this sort has already emerged. The technology in question can monitor the Earth’s entire landmass every single day. It’s the brainchild of a San Francisco–based company called Planet, founded by three idealistic former NASA scientists named Will Marshall, Robbie Schingler, and Chris Boshuizen.

Their headquarters resides in an unprepossessing warehouse in the gritty South of Market neighborhood. The tableau inside is textbook Silicon Valley: more than 200, mostly young techies in aggressively casual dress hunched silently over their keyboards in an open work space, aside from a few conference rooms named after some of the company’s heroes—among them, Galileo, Gandhi, and Al Gore. I sat in one of them overlooking the upscale employee cafeteria, where lunch would later be followed by a happy hour of Napa wines and California microbrews.

Marshall and Schingler joined me. The former is a lanky Brit with wire-frame glasses; the latter, a broad-shouldered and easygoing Californian. Both are 39 and seemed fully recovered from their dinner the previous evening to celebrate the fifth anniversary of when they started working full time at Planet. At NASA they had been captivated by the idea of taking pictures from space, especially of Earth—and for reasons that were humanitarian rather than science based.

They experimented by launching ordinary smartphones into orbit, confirming that a relatively inexpensive camera could function in outer space. “We thought, What could we do with those images?” Schingler said. “How can we use these things for the benefit of humanity? List the world’s problems: poverty, housing, malnutrition, deforestation. All of these problems are more easily addressed if you have more up-to-date information about our planet. Like you wake up in a few years and you find there’s a hole in the Amazon forest. What if we could have supplied information about this more rapidly to the Brazilian government?”

They experimented by launching ordinary smartphones into orbit, confirming that a relatively inexpensive camera could function in outer space. “We thought, What could we do with those images?” Schingler said. “How can we use these things for the benefit of humanity? List the world’s problems: poverty, housing, malnutrition, deforestation. All of these problems are more easily addressed if you have more up-to-date information about our planet. Like you wake up in a few years and you find there’s a hole in the Amazon forest. What if we could have supplied information about this more rapidly to the Brazilian government?”

In storybook fashion, Marshall and Schingler developed their first model in a garage in Silicon Valley. The idea was to design a relatively low-cost, shoe box–size satellite to minimize the military-scale budgets often required for designing such technology—and then, as Marshall told me, “to launch the largest constellation of satellites in human history.” By deploying many such devices, the company would be able to see daily changes on the Earth’s surface in totality.

In 2013 they launched their first satellites and received their first photographs, which provided a far more dynamic look at life around the world than previous global mapping imagery. “The thing that surprised us most,” said Marshall, “is that almost every picture that came down showed how the Earth was changing. Fields were reshaped. Rivers moved. Trees were taken down. Buildings went up. Seeing all of this completely changes our concept of the planet as being static. And instead of just having a figure about how much a country has been deforested, people can now be motivated by pictures that show the deforestation taking place.”

SATELLITES

More than 1,700 satellites orbit above us, some as much as 100,000 miles overhead. They collect images and other data, broadcast information, track our locations, and even listen to our conversations. U.S. public institutions and companies operate most satellites, with commercial launches already far outstripping the government’s.

UNITED STATES n.814 – (Planet, this company’s fleet has grown from just four satellites in 2013. 202 satellites)

CHINA n.205 – (People’s Liberation Army 39 satellites)

RUSSIA n.140 – (Ministry of Defense 81 satellites)

OTHERS n.578

Earth observation: collect data for intelligence gathering and environmental monitoring

Communications: send point-to-point and broadcast transmissions

Navigation, timing, and tracking: track ships, aid navigation, and synchronize timing for computer systems

Technology development: test new technology and develop experimental payloads

Space science/other: collect data about space and pursue other scientific inquiries

Jason Treat and Ryan T. Williams, Ngm Staff. Sources: Union of Concerned Scientists; Planet

Today Planet has more than 200 satellites in orbit, with about 150 it calls Doves that can image every bit of land every day when conditions are right. Planet has ground stations as far away as Iceland and Antarctica. Its clients are just as varied. The company works with the Amazon Conservation Association to track deforestation in Peru. It has provided images to Amnesty International that document attacks on Rohingya villages by security forces in Myanmar. At the Middlebury Institute’s Center for Nonproliferation Studies, recurring global imaging helps the think tank watch for the sudden appearance of a missile test site in Iran or North Korea. And when USA Today and other publications wanted an aerial image of the Shayrat air base in Syria before and after it was bombed by the U.S. military last April in retaliation for a chemical attack on a rebel-held Syrian town, the news organizations knew whom to call.

Those are pro bono clients. Its paying customers include Orbital Insight, a Silicon Valley–based geo-spatial analytics firm that interprets data from satellite imagery. With such visuals, Orbital Insight can track the development of road or building construction in South America, the expansion of illegal palm oil plantations in Africa, and crop yields in Asia. In the company’s conference room, James Crawford, the chief executive, opened his laptop and showed me aerial views of Chinese oil tanks, with their floating lids indicating they were about three-quarters full. “Hedge funds, banks, and oil companies themselves know what’s in their tanks,” he said with a sly grin, “but not in others’, so temporal resolution is extremely important.” Crawford’s firm also employs Planet’s optical might to charitable ends. For example, it conducts poverty surveys in Mexico for the World Bank, using building heights and car densities as proxies for economic well-being.

Meanwhile, Planet’s marketing team spends its days gazing at photographs, imagining an interested party somewhere out there. An insurance company wanting to track flood damage to homes in the Midwest. A researcher in Norway seeking evidence of glaciers eroding. But what about … a dictator wishing to hunt down a roving dissident army?

Here is where Planet’s own ethical guidelines would come into play. Not only could it refuse to work with a client having malevolent motives, but it also doesn’t allow customers to stake a sole proprietary claim over the images they buy. The other significant constraint is technological. Planet’s surveillance of the world at a resolution of 10 feet is sufficient to discern the grainy outline of a single truck but not the contours of a human. Resolution-wise, the current state of the art of one foot is supplied by another satellite imaging company, DigitalGlobe. But for now, only Planet, with its formidable satellite deployment, is capable of providing daily imagery of Earth’s entire landmass. “We’ve run the proverbial four-minute mile,” Marshall said. “Simply knowing it’s possible doesn’t make it any easier.”

Still, Planet has blazed a trail. Others someday will follow it. When they do, how will they harness the power to see so much of the globe, every single day? Will their aims be as benevolent as those of Planet? Will they try to perfect satellite photography that’s higher in resolution and thus in invasiveness? Marshall doesn’t see how this is possible. “To identify a person from 300 miles away, you’d need a camera the size of a bus,” he told me. And in any event, he added, an American firm seeking to accomplish that would encounter considerable federal regulatory hurdles.

Of course, regulations can be changed. So can the boundaries of our technological limits. Just a year or two ago, the owner of the largest number of functioning satellites in orbit was the U.S. government, with roughly 170. Now Planet prevails over the heavens in greater numbers than the most powerful nation on Earth.

Who is next in line to be the Biggest Brother?

On a bracing autumn evening in San Francisco, I returned to Planet to see the world through its all-encompassing lens. More than a dozen clients would be there to show off how they’re using satellite imagery—what it meant, in essence, to see the world as it’s changing.

I zigzagged among semicircles of techies gathered raptly around monitors. Everywhere I looked, the world came into view. I saw, in the Brazilian state of Pará, the dark green stretches of the Amazon jungle flash red, prompting automatic emails to the landowners: Warning, someone is deforesting your land! I saw the Port of Singapore teem with shipping activity. I saw the croplands of southern Alberta, Canada, in a state of flagging health. I saw an entire network of new roads in war-wracked Aleppo, Syria—and for that matter, a new obstruction in one of those roads, possibly a crater from a bomb attack. I saw oil well pads in Siberia—17 percent more than in the previous year, a surprising sign of stepped-up production that seemed likely to prompt frantic reassessments in the world’s oil and gas markets.

….

As I walked back to my hotel, I thought about the two moped riders in Islington, as I often had in the months since I surveilled them. I wondered if they had been arrested. I wondered if they were guilty of anything at all, apart from the crime of being conspicuously interesting on an otherwise dull morning. I wondered if they would ever know that unseen strangers had been watching them, just as a stranger might now be watching me—someone somewhere squinting into a CCTV monitor at the spectacle of a lone figure walking fast on a dark and otherwise vacant street on a chilly night without a coat on, as if in flight from something.

Robert Draper is a contributing writer for the magazine. His previous feature, about young technology entrepreneurs in Africa, ran in the December 2017 issue.